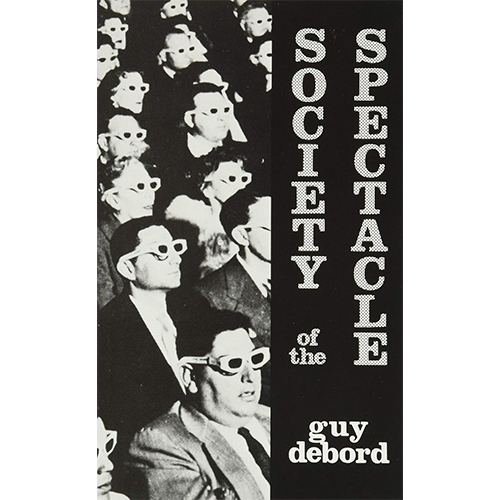

Guy Debord

Society of the Spectacle

The Society of the Spectacle is a Debordian analysis of modern life. It’s a prescient read as Debord introduces the concept of the spectacle, its many facets and its impact on our lives. He describes the spectacle as an affirmation of appearances and an identification of all human social life with appearances, though his definition goes in various directions as you venture further through the book. It is a book that will most likely always be relevant, and though not the most concise, it is difficult to not find parts that are deeply resonant.

We are bombarded, more than ever, by a multitude of images, screens and objects which all exist in the spectacle, making it the leading production of present-day society.

The passive acceptance that the spectacle demands is effectively imposed by its monopoly of appearances, given its manner of appearing without allowing any reply. Debord explains that its sole message is ‘what appears is good; what is good appears’.

I.

Debord presents a historical analysis of this great shift in society. He views the first stage of the spectacle aligning with the transition in the way we think about fulfilment. It was no longer equated with what one was, but with what one possessed. However, the present stage is now a transition into appearance. Prestige and ultimate purpose must now be derived from appearances, whilst at the same time all individual reality has become social.

The spectacle’s job is to use various specialised meditations in order to show us a world that can no longer be directly grasped. This is quite indicative of our reality as the world seems so much more accessible now, and though that’s true to some extent there is an illusory aspect to it.

It is the ruling order’s non-stop discourse about itself, its never ending monologue of self-praise, its self-portrait at the stage of totalitarian domination of all aspects of life. Debord views the reigning economic system as a vicious circle of isolation and that the spectacle creates swathes of loneliness among those who consume.

The spectacle’s social function is the concrete manufacture of alienation. The growth generated by an economy developing for its own sake can be nothing other than a growth of the very alienation that was at its origin. As labour is increasingly rationalised and mechanised, this subjugation is reinforced by the fact that people’s activity becomes less and less active and more and more contemplative.

‘The more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more he identifies with the dominant image of need, the less he understands his own life and his own desires.’

The spectacle is dominant in every aspect of our lives, both our working life and in leisure. This is the transition from a worker to a consumer.

‘Once his workday is over, the worker finds himself seemingly treated like a grown-up, with a great show of politeness, in his new role as a consumer.’

It takes charge of the worker’s leisure and humanity simply because the economy now can and must dominate those spheres. The spectacle is a permanent opium war designed to force people to equate goods with commodities and to equate satisfaction with a survival that expands according to its own laws.

Consumers are filled with religious fervour for the sovereign freedom of commodities whose use has become an end in itself. Waves of enthusiasm for particular products are propagated by the media. A film sparks a fashion craze, a magazine publicises night spots, which in turn spin off different lines of products. All of this is useful for only one purpose: producing habitual submission.

Commodity abundance represents a total break in the organic development of social needs. Its mechanical accumulation unleashes an unlimited artificiality which overpowers any living desires. The cumulative power of this ends up falsifying all social life. The object that was prestigious in the spectacle becomes mundane as soon as it is taken home by the consumer.

‘[The spectacle] may gild poverty, but it cannot transcend it.’

Debord views the spectacle as the flip side of money and as an abstract general equivalent of all commodities. Where money has dominated as the representation of universal equivalence, the spectacle is the modern complement of money. It is money one can only look at, because all use has already been exchanged.

The necessity for boundless economic development which now dominates our world means replacing the satisfaction of primary human needs (now scarcely met) with an incessant fabrication of pseudo-needs, all of which ultimately come down to the single-pseudo need of maintaining the reign of the economy.

Debord gives his take on the many facets of the spectacle. He deems celebrities as spectacular representations of human beings who project a general banality into images of permitted roles. They serve as superficial objects that people can identify with in order to compensate for the fragmented productive specialisations that they actually live.

The function of these celebrities is to act out various lifestyles or sociopolitical viewpoints in a full, totally free manner. They embody the inaccessible results of social labour by dramatising the by-products of that labour which are magically projected above it as ultimate goals: power and holidays.

Social media is a personification of the spectacle in a way, generating fervent allegiance to ‘quantitative trivialities’. The admirable people who personify the system are well known for not being what they seem. They attain greatness by stooping below the reality of the most insignificant individual life and everyone knows it. The false choices offered by spectacular abundance develop into a struggle between illusory qualities.

IV.

History obviously plays an important role in the development of the spectacle. Historical time flows independently above its own static community. Writing is the rulers’ weapon. With writing there appears a consciousness that is no longer carried and transmitted directly among the living. It becomes an impersonal memory, the memory of the administration of society.

‘Writings are the thoughts of the state; archives are its memory.’

The chronology that an authority offered to its subjects, who were supposed to accept it as the earthly fulfilment of mythic commandments, was destined to be transcended and transformed into conscious history. However, for this to happen large groups of people had to have experienced real participation in history. This personifies our current timeline where we are increasingly more able to participate in history, therefore history has become much less linear.

V.

In the final chapters Debord talks about innovation and society without community. In the struggle between innovation and tradition, innovation always wins which is easy to see in modern day. Cultural innovation is generated by nothing other than the total historical movement. In all these areas the goal remains the same: to restructure society without community. This is similar to the way James C. Scott describes high-modernism in Seeing Like A State.

This book sheds an important light on the darker parts of our society, however viewing the world in this way with vague answers makes everything seem somewhat hopeless. It’s not difficult to understand why all these French philosophers were depressed.

If you want to explore it in more depth I’d recommend this book review which does a much better job with depth and context than I do.

We are bombarded, more than ever, by a multitude of images, screens and objects which all exist in the spectacle, making it the leading production of present-day society.

The passive acceptance that the spectacle demands is effectively imposed by its monopoly of appearances, given its manner of appearing without allowing any reply. Debord explains that its sole message is ‘what appears is good; what is good appears’.

I.

Debord presents a historical analysis of this great shift in society. He views the first stage of the spectacle aligning with the transition in the way we think about fulfilment. It was no longer equated with what one was, but with what one possessed. However, the present stage is now a transition into appearance. Prestige and ultimate purpose must now be derived from appearances, whilst at the same time all individual reality has become social.

The spectacle’s job is to use various specialised meditations in order to show us a world that can no longer be directly grasped. This is quite indicative of our reality as the world seems so much more accessible now, and though that’s true to some extent there is an illusory aspect to it.

‘The spectacle is the opposite of dialogue. It is not merely a matter of images, nor even of images plus sounds. It is whatever escapes people’s activity, whatever eludes their practical reconsideration and correction.’

It is the ruling order’s non-stop discourse about itself, its never ending monologue of self-praise, its self-portrait at the stage of totalitarian domination of all aspects of life. Debord views the reigning economic system as a vicious circle of isolation and that the spectacle creates swathes of loneliness among those who consume.

The spectacle’s social function is the concrete manufacture of alienation. The growth generated by an economy developing for its own sake can be nothing other than a growth of the very alienation that was at its origin. As labour is increasingly rationalised and mechanised, this subjugation is reinforced by the fact that people’s activity becomes less and less active and more and more contemplative.

‘The more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more he identifies with the dominant image of need, the less he understands his own life and his own desires.’

II.

The spectacle is dominant in every aspect of our lives, both our working life and in leisure. This is the transition from a worker to a consumer.

‘Once his workday is over, the worker finds himself seemingly treated like a grown-up, with a great show of politeness, in his new role as a consumer.’

It takes charge of the worker’s leisure and humanity simply because the economy now can and must dominate those spheres. The spectacle is a permanent opium war designed to force people to equate goods with commodities and to equate satisfaction with a survival that expands according to its own laws.

Consumers are filled with religious fervour for the sovereign freedom of commodities whose use has become an end in itself. Waves of enthusiasm for particular products are propagated by the media. A film sparks a fashion craze, a magazine publicises night spots, which in turn spin off different lines of products. All of this is useful for only one purpose: producing habitual submission.

Commodity abundance represents a total break in the organic development of social needs. Its mechanical accumulation unleashes an unlimited artificiality which overpowers any living desires. The cumulative power of this ends up falsifying all social life. The object that was prestigious in the spectacle becomes mundane as soon as it is taken home by the consumer.

‘[The spectacle] may gild poverty, but it cannot transcend it.’

Debord views the spectacle as the flip side of money and as an abstract general equivalent of all commodities. Where money has dominated as the representation of universal equivalence, the spectacle is the modern complement of money. It is money one can only look at, because all use has already been exchanged.

The necessity for boundless economic development which now dominates our world means replacing the satisfaction of primary human needs (now scarcely met) with an incessant fabrication of pseudo-needs, all of which ultimately come down to the single-pseudo need of maintaining the reign of the economy.

III.

Debord gives his take on the many facets of the spectacle. He deems celebrities as spectacular representations of human beings who project a general banality into images of permitted roles. They serve as superficial objects that people can identify with in order to compensate for the fragmented productive specialisations that they actually live.

The function of these celebrities is to act out various lifestyles or sociopolitical viewpoints in a full, totally free manner. They embody the inaccessible results of social labour by dramatising the by-products of that labour which are magically projected above it as ultimate goals: power and holidays.

‘The agent of the spectacle who is put on stage as a star is the opposite of an individual; he is clearly the own enemy of his own individuality as the individuality of others.’

Social media is a personification of the spectacle in a way, generating fervent allegiance to ‘quantitative trivialities’. The admirable people who personify the system are well known for not being what they seem. They attain greatness by stooping below the reality of the most insignificant individual life and everyone knows it. The false choices offered by spectacular abundance develop into a struggle between illusory qualities.

IV.

History obviously plays an important role in the development of the spectacle. Historical time flows independently above its own static community. Writing is the rulers’ weapon. With writing there appears a consciousness that is no longer carried and transmitted directly among the living. It becomes an impersonal memory, the memory of the administration of society.

‘Writings are the thoughts of the state; archives are its memory.’

The chronology that an authority offered to its subjects, who were supposed to accept it as the earthly fulfilment of mythic commandments, was destined to be transcended and transformed into conscious history. However, for this to happen large groups of people had to have experienced real participation in history. This personifies our current timeline where we are increasingly more able to participate in history, therefore history has become much less linear.

V.

In the final chapters Debord talks about innovation and society without community. In the struggle between innovation and tradition, innovation always wins which is easy to see in modern day. Cultural innovation is generated by nothing other than the total historical movement. In all these areas the goal remains the same: to restructure society without community. This is similar to the way James C. Scott describes high-modernism in Seeing Like A State.

This book sheds an important light on the darker parts of our society, however viewing the world in this way with vague answers makes everything seem somewhat hopeless. It’s not difficult to understand why all these French philosophers were depressed.

If you want to explore it in more depth I’d recommend this book review which does a much better job with depth and context than I do.