Essay:

The Psychology of Aesthetics

One of the fundamental joys of being alive is the appreciation of the physical things around us. We’re surrounded by a world of beauty, ugliness and everything in between. What determines our sensibility towards these things? Why do we think some things are ugly and some things are beautiful? As you can imagine these are the types of questions which have been asked for millennia. However, only in the past few centuries has there been proper research into why this is. We have some answers about the way in which we determine beauty, however we’ve barely even got to the surface, let alone scratched it.

The word ‘aesthetics’

There are two main clusters of meaning when we refer to aesthetics. Firstly, there is the process of sensation which is derived from words such as anaesthetic, the absence of sensation. However, the second cluster is the one that dominates Western culture, which is primarily discussed in the humanities, philosophy and art history. This is the idea of a bipolar beautiful/ugly dichotomy which is used to address the aesthetics of objects and nature. This may be due to the fact that it is taken for granted that a sensory component is part of aesthetic processing and that most qualitative aspects encompass the idea of a beautiful/ugly dichotomy.

History

Throughout history, there have been many questions considered in respect to our perception of beauty in the world. For millennia, philosophers have pondered the nature of beauty and taste, however there has been a lack of definitive methods to measure and understand exactly how our aesthetic appreciation is formed.

There have been notable discoveries as to why we find some things more aesthetically pleasing than others, such as the Golden Ratio. In maths, two quantities are in the Golden Ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities, and its presence is believed to make something more aesthetically pleasing.

The ratio has been found across the world and used by the likes of Leonardo Da Vinci, Salvador Dali and Le Corbusier, but the reasons why have led to a range of psychological experiments investigating the relationship between the human perception of beauty and mathematics.

Modern research concerning the psychology of aesthetics can be traced back to 1876 when Gustav Fechner published ‘Vorschule der Aesthetik’, which translates to ‘Introduction to Aesthetics’. Much of Fechner’s work involved the Golden Ratio and many experiments that followed sought it out in respect to fields such as group preferences and facial attractiveness.

Following Fechner there were a few notable contributions that had a strong influence on the psychology of aesthetics. One such is Gestalt psychology which helped to introduce the idea that human perception is not just about seeing what is actually present in the world around; it’s heavily influenced by our motivations and expectations.

Despite a lot of controversy surrounding the Golden Ratio, especially in respect to the arts, the psychology of aesthetics is one of the oldest research areas in psychology, and Vorschule der Aesthetik was influential at the time because it argued for an empirical ‘aesthetics from below’ approach that assembles pieces of objective, empirical knowledge. This tradition is still followed and most research methods are derived from this philosophy. The approach separates objective observations from a third person perspective and individual, subjective experiences whilst still deriving relationships between the two.

Objective observations

The current measures for objective observations are done mainly through methods using technology, such as event-related brain potentials (ERPs) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRIs).

In some ERP studies participants were asked to judge the beauty of male and female faces. Both men and women took less time to judge male faces than female faces. Female faces required a longer time to be evaluated and were judged taking a larger number of cues into consideration.

Some fMRI studies have investigated the beauty of geometrical shapes. The results confirmed the influence of symmetry and complexity on aesthetic judgements. The technical reason for this is that beautiful judgments enhance the blood oxygenation level-dependent signals not only in the frontomedial cortex, but also in the left intraparietal sulcus of the symmetry network. These findings indicate that aesthetic judgements of beauty rely on a network that partially overlaps with the network underlying evaluative judgements on social and moral cues.

It’s rather difficult to get conclusive evidence from objective observations because there’s such a range of objects and factors to be considered. It’s easier to understand the way humans react to simple geometrical objects, however it becomes a lot more complicated when more complex objects are introduced and results tend to be extrapolated or unclear.

Subjective experiences

The contrasting empirical method of aesthetic appreciation is an individual's own subjective experience. This is much more difficult to measure and is based upon an individual's own report. This also enters into the realm of the philosophy of aesthetics which is beyond the scope of this piece.

There are many determinants of aesthetic experience, some of the main ones being symmetry, complexity, novelty, proportion, semantic content and mere exposure.

There are also many factors which can influence aesthetic judgements such as a person’s emotional state, the interestingness of the stimulus, appeal to social status or financial interest and most significantly educational, historical, cultural or economic background. Therefore, aesthetic experiences and behaviour are subject to a complex network of stimulus, person and situation related influences.

These factors illustrate how complex and multifaceted aesthetic appreciation is; for the most part it is impossible to pin it down to one single element. Art displayed in a museum is a key example of this as it involves almost all the factors simultaneously combined with each individual's neuroanatomical reaction.

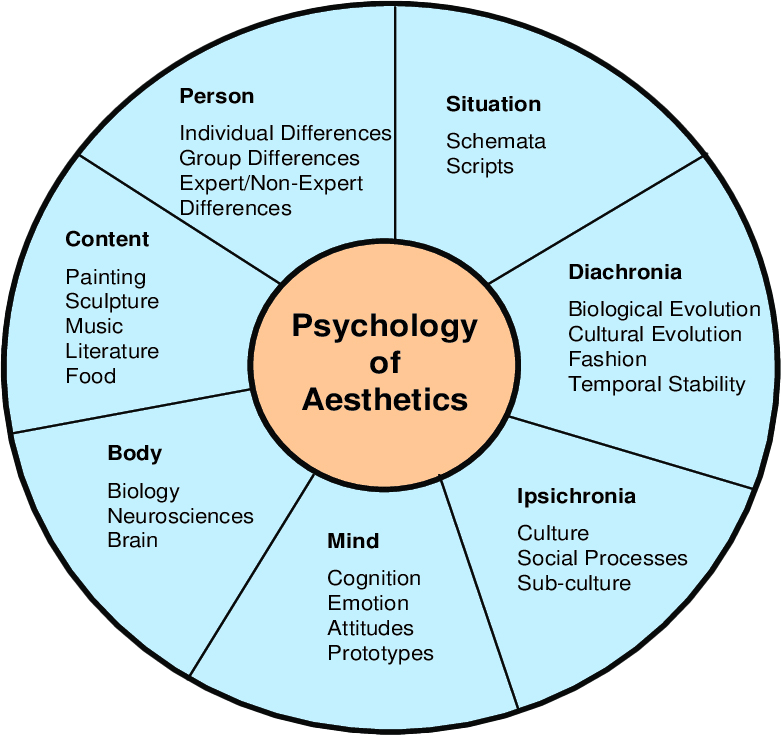

A Framework for the Psychology of Aesthetics

Diachronia and ipsichronia are probably the least intuitive to understand. They both cover the entire realm of aesthetic processing, focusing mainly on the cultural elements. They concentrate on comparisons within a given time period, which includes the perspective that takes changes over time into account.

This embodies questions such as why do individuals produce elaborate tools and weapons if they are not intended for use? Why do faces have to show a certain degree of symmetry to be perceived as beautiful? What is the contribution of evolution to the development of our aesthetic faculties and skills?

Despite our evolution and biological design being a key factor in aesthetics, many aspects of aesthetic appreciation are culture-relative. This includes the design of urban space, school environments and procedures in cosmetics. To go even further, there are numerous examples of aesthetic preferences being contingent on a given culture or subculture, from tattoos and piercings to dress codes and hair styles.

The third vantage point, mind, is the view of aesthetic processing from the perspective of modern academic psychology. This can be related to individual subjective experiences and applies to the psychology of emotions, posing questions such as how does mood influence aesthetic judgement? It also borders on the philosophical elements of aesthetics, for example the distinction between reflecting and determining aesthetic judgments and the conception of artificial versus natural beauty.

The body refers to aesthetic processing according to somatic aspects, therefore biology and neuroscience are the main areas of focus. The distinction between the body and mind is that the vantage point of the body centres around objective observations from a third person perspective and research includes those previously mentioned such as fMRIs and ERPs.

Content refers to aesthetic processing for a large number of entities. Aesthetic appreciation is very context dependent and these different realms of content may show vastly different characteristics that in turn lead to different determiners of aesthetic processing.

The sixth vantage point is person and this perspective focuses on individual processing characteristics and preferences. There is not much research in this area and relatively little is known about inter-individual differences of aesthetic processing within homogeneous groups. This is strongly related to the factors that contribute to diachronia and ipsichronia.

Finally, the last vantage point is situation. This is the combination of how a given time and place affects aesthetic processing. For instance, the difference in the way a can of soup is perceived in a supermarket versus a museum.

All seven vantage points open up an enormous amount of scope for a variety of research relating to the psychology of aesthetics. It’s such a broad topic that there are many specialities which focus on one aspect.

For example, experimental aesthetics mainly deals with research on art, as well as artefacts in a wider sense, whereas human attractiveness research is mainly dealt with in social psychology. To extrapolate further, there are many overlapping areas that cover numerous aspects of aesthetic preferences such as the psychology of music, anthropology, evolutionary biology and architecture.

The seven vantage points allow for an overarching framework which can piece together various aspects of research at a high level. Therefore, it has the potential to make it easier to link research back into a central theme and to understand how it contributes to the psychology of aesthetics as a whole.

Conclusion

Determining the origins and causes of aesthetic sensibility is incredibly difficult because of the number of intersecting factors at play in the formation of preferences. The further you explore the more questions there are to ask and its expansive nature covers so many overlapping topics. There is still a long way to go in order to better understand the nature of beauty and everything that comes along with it.

Fechner’s approach will continue to be used to develop our understanding as we attempt to align and contrast the differences between objective observations and the subjective experiences of the individual. There are some problems with the methodology, most notably the conflict between the degree of experimental control and the generalisability of the findings.

The psychology of aesthetics is, after all, a combination of nature and nurture, and Jacobsen’s framework has the potential to encompass all research on the topic into a unified whole, giving more context to individual research across a number of disciplines. It also serves to show at a high level how complex and multifaceted the area is whilst including other extensive areas such as the philosophy of aesthetics.

Further reading...

- Beauty and the brain: culture, history and individual differences in aesthetic appreciation

- Bridging the Arts and Sciences: A Framework for the Psychology of Aesthetics

- Fechner (1866): The Aesthetic Association Principle

- Aesthetic activities and aesthetic attitudes: Influences of education, background and personality on interest and involvement in

- The golden ratio and aesthetics

- Gestalt Laws of Perceptual Organization and Our Perception of the World

-

Introduction to the Psychology of Aesthetics

- The Beginning of Infinity